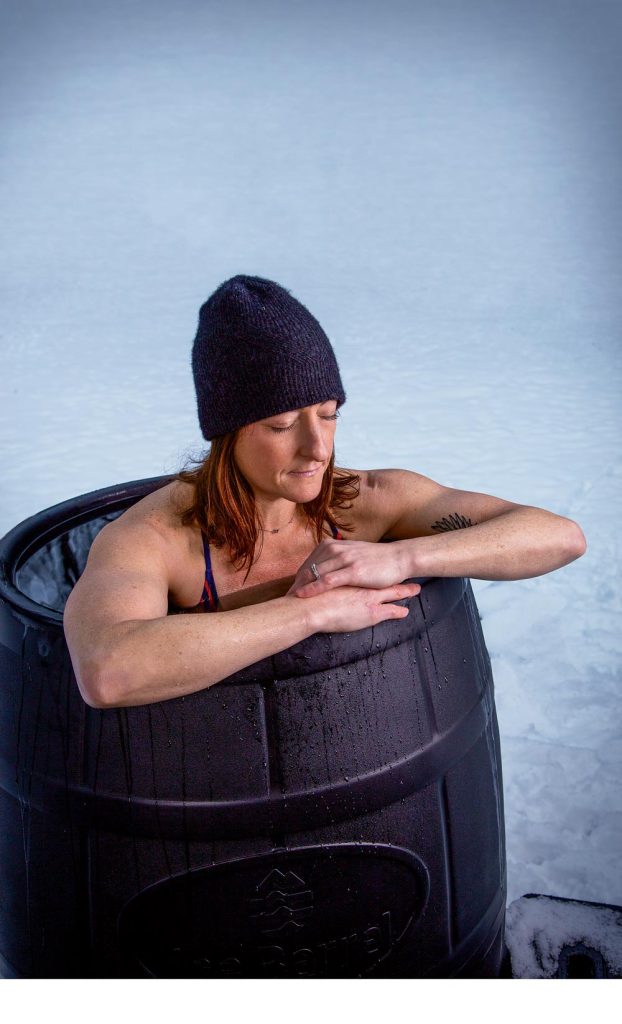

Dip in your toes and they sting. Then submerge your legs, and your ankles start to ache. Slide your torso into the icy water, and it takes your breath away. This was how the first day of my ice bath practice went. After two minutes in the 105-gallon specialized barrel that I keep outside, filled with 46-degree Fahrenheit water sourced from my rural Vermont well and cooled further by 40 pounds of ice, the experience became more tolerable—albeit far from enjoyable.

Ever since my time as a high school cross country skier, I’ve been prone to inflammation. I’ve had tendinitis of varying severity in almost all of my major joints, including achilles tendinitis that kept me from running farther than five miles for more than four years. These recurring injuries piqued my interest in ice bathing, something that even after decades spent in and around the competitive ski world I knew very little about.

For a lot of skiers, a session in the sauna is as much a part of the sport as a golfer’s trip to the clubhouse bar. Perhaps it’s because of their Nordic roots that saunas are so popular among skiers, but conduct a Google search or visit a ski club and you’d be hard pressed—aside from icing for injuries—to find a strong connection between cross country skiing and cold therapy. But could competitive Nordic skiers benefit from ice baths as a tool for recovery? Based on the research about the practice as related to other sports—CrossFit in particular—it seems likely.

Dr. Rob Williams is the co-founder of a Vermont-based business called Peak Flow, which educates athletes, and others, on cold therapy and breathwork practices. He explains the method in an email: “By activating a biological process known as ‘hormesis’—voluntary positive stress regularly applied in titrated doses, followed by active recovery (which is vital)—an endurance athlete can cultivate deeper resilience of mind, body and spirit.” By doing this, he adds, you can reduce inflammation, decrease muscle soreness, open up the circulatory system and strengthen the vascular, immune and respiratory systems.

I was able to work up to approximately 12 minutes in a 44- to 46-degree Fahrenheit ice bath.

Other studies about continued cold therapy point to additional physiological changes that would benefit competitive skiers, like higher heart rate variability, better cold acclimation and a higher quality of sleep (a vital part of the recovery process). One of the preeminent practitioners of cold therapy is Wim Hof, an athlete known for his exploits in extremely cold environments and who once held a Guiness World Record for the farthest swim under ice (66 meters, or 216 feet). He considers cold exposure one of the three pillars of his eponymous method, which, according to his website, “is a way to keep your body and mind in its optimal natural state.”

Ice bathing regularly has also been shown to improve mood and reduce anxiety, due to the hormones released during cold exposure; in some cases, ice baths have even been linked to weight loss and a lower body-fat percentage.

Aside from what can be found in studies, anecdotes suggest that ice bathing leads to a better quality of life. “After five minutes of ice bathing every morning, I feel ready for whatever the day may throw at me,” writes Williams. “Plus, the feeling of the body warming up naturally after the ice is a beautiful and powerful sensation—one I carry into the day, like my whole mind and body are resonating with a renewed sense of clarity, focus and alertness.”

As for me, I was able to work up to approximately 12 minutes in a 44- to 46-degree Fahrenheit ice bath, trying to spend one minute longer each time I dipped. I prioritized sessions after long interval or strength workouts, and I can say that I at least felt better. I don’t know if I can attribute the result entirely to the practice, but I was noticeably less sore. Moreover, my resting heart rate steadily decreased and my average heart rate variability increased.

Could the results be a placebo effect, or due to better-structured training? Possibly. But I was also noticeably more alert and awake after an ice bath, especially when I took one first thing in the morning or after an early training session, I didn’t feel like I needed that extra cup of coffee, even if the kids (and therefore everyone) had had a rough night of sleep.

I’m not training for anything in particular; I just want to get more fit and healthy. I run and bike in the summer and ski in the winter, with some semblance of a workout structure because it feels good to be in that routine. And now, after seven months, I honestly can say I look forward to that icy dip, too.

THE GEAR

Ice Barrel

This 105-gallon, 42-inch-tall heavy-duty plastic tub is designed to be an easy method for ice bathing. When empty, the barrel weighs 55 pounds and is easy to move around. When full (in my case, with approximately 75 gallons of water and ice), it’s a beast and essentially inert—a good thing when you’re propped on top and lowering inside. Also included is a lid and UV-protective cover. At six feet tall, I was able to easily climb in and out of the barrel with the included step stool (though shorter people may find doing so a challenge).The Ice Barrel comes in black recycled plastic or tan (non-recycled) plastic. $1,200, icebarrel.com

Garmin Fenix 7

For tracking my heart rate and other measures before and after ice bathing, I use the newest model in Garmin’s Fenix line, the 7. It features a longer-lasting battery and much improved metrics for stats like pulse oximetry, heart-rate variability, perceived energy remaining (thanks to Garmin’s proprietary Body Battery function, which estimates how much energy you have left before reaching exhaustion) and menstrual cycle tracking for women. Additionally, the Fenix 7 comes in a version that includes solar battery charging. Like some of its predecessors, the 7 includes access to Garmin’s mapping software (through the app and website) and map display, as well as a wrist-based heart rate monitor. $700–$900, garmin.com

This story first appeared in the Late Winter 2023 issue of Cross Country Skier (42.3).