On February 24, 2021, Ernie St. Germaine skied the American Birkebeiner, just as he’s done for the past 47 years. This time, however, because of the pandemic, he skied 45 kilometers on a course of his own choosing. He still wore his red bib with the No. 3 on it, which identifies him as a Founder, an honor given to those who skied the first 10 American Birkebeiners. He’s the only Founder who still skis the race.

It was a sparkling and cold morning in northern Wisconsin, and St. Germaine, who lives near Hayward, waited until the temperature was 4°, knowing the sun would warm things quickly. He started near the midpoint of the long Birkie Trail, on Key Log Crossing, a bridge that spans County Highway OO. He planned to ski five and a half kilometers north to Boedecker Road, even though it has some of the hilliest sections, because it was friend and fellow Founder Dave Landgraf’s favorite part of the trail.

St. Germaine stood on the bridge and thought of Landgraf, who was struck by a car while cycling in 2011 and killed. He thought of Tony Wise, the true founder of the Birkebeiner, and he thought about his grandparents and about other Founders who have passed on and will always be his heroes. With a strong double pole push, he set off.

St. Germaine’s daughter, Stephanie, and a friend, Carol, were his support crew. At Boedecker Road they provided food and hydration and, after he turned back south, they met him at trail crossings, guided by a tracking app on St. Germaine’s watch. Because of the relaxed pace of his solo ski, he spent more time visiting with people.

“Nine guys in a group at Gravel Pit saw my bib and wanted to shake my hand,” he says. “One said it had been his dream to meet me.”

St. Germaine shakes his head when he talks about this kind of recognition. He gives the impression that he feels morally obligated to continue racing, to be a role model and hero for others, especially children. He made his way along the trail, trying different skis that Stephanie brought to him as the temperature rose, eventually returning north to finish where he started. His self-reported race time was 4:40:16, using the classic technique.

An Accidental Start

St. Germaine never planned to ski the first Birkie. An alpine skier, he put on cross country skis for the first time, at the age of 25, exactly one week before the inaugural race on February 24, 1973. The extent of his practice? He tried out Lyman Williamson’s skinny skis for 20 minutes in the driveway. Williamson, a friend of St. Germaine’s grandfather, was going to ski the 55-kilometer race organized by his friend Tony Wise, owner of the Telemark Lodge in Cable, but his plans were nixed.

St. Germaine remembers that day well. “Lyman was 72, and his wife said no. He turned to me and said, ‘My boy, you are going to represent me.’ I suppose I’ve been representing him every year since.”

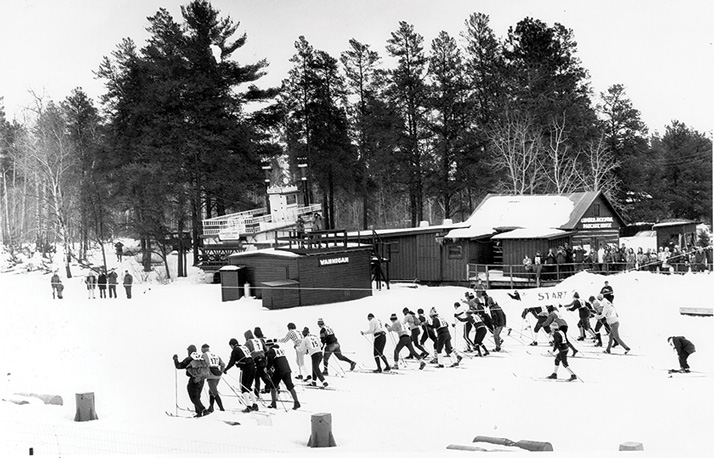

That year the race began on Lake Hayward. At the start, St. Germaine called out to Williamson, “Where are we going?” Recalls St. Germaine now, “I had no idea. I thought we were just going out on the lake.” Williamson called back, “Don’t worry. I’ll pick you up at Telemark.”

“I just followed the snowmobile track with ski tracks on it,” St. Germaine relates. “When we got close to Telemark, I could hear music from the chalet. I was so tired. There were two long climbs to go and my skis slipped, and Dave Landgraf and I were on all fours. Karl Andresen herringboned up behind us and said, ‘Get the hell out of the way.’ No way did we want him to beat us. Dave and I went down the next hill together and crashed into a bank. Karl skied by and finished well in front of us. Not knowing how to stop, Dave and I crashed at the finish line, laughing. There were two posts and a card table, and Jeanette Vortanz was handing out gold NASTAR ribbons. She said, ‘The devil got into you boys!’”

A Reprieve and a Focus

That’s the storied beginning of St. Germaine’s long history with the race. Now, if among the tens of thousands who have skied the American Birkebeiner you mention “Ernie,” people know whom you mean. He might seem like many cross country skiers: fit and motivated to train, lanky, professionally successful. But in a homogeneous demographic like that of Nordic skiing, St. Germaine stands out. His father was from the Lac du Flambeau Band of the Ojibwe, who have a reservation some 100 miles east of Hayward. His mother was from the Lac Courte Oreilles Band, on a reservation just southeast of Hayward. He is grateful to have been raised by his grandparents, which was natural in the Indian way, he says. They directed how he lives and how he takes care of Mother Earth.

In conversation, St. Germaine radiates a small smile, or he may emit a barely discernable and rare look of concern. He flashes his eyes if he disagrees and offers a tiny nod when he is in agreement. Sometimes he uses a metaphor to explain a situation, or he’ll tell a brief story, or he’ll show a photo on his phone. Then he’ll pause to let things sink in without further explanation.

The Birkie is both a bright beacon and a stronghold in his life, for reasons the average skier may never have considered. “Not a single day of my life has gone by that I haven’t felt racism or been subjected to it,” says St. Germaine. “Sometimes it’s subtle, sometimes it’s incredibly blatant.” This is when his eyes flash. “The only place I haven’t felt or seen racism is in the Birkebeiner.” His face softens here, and he talks about sports drawing people together, of the shared experience that brings forth a kind and loving brotherhood and sisterhood.

On skis, he easily moves with the confidence of someone with a life-long devotion to fitness. He’ll be 74 soon, and people often ask him how he does it. St. Germaine attributes his endurance to his resolute mindset. It helps that he has an athlete’s metabolism. “At age 25 I did not have an ounce of fat,” he says. He still doesn’t. And he refers, quietly, to the traditional teachings of his tribal elders, which include living a positive and healthy life.

Early in the season St. Germaine focuses on technique, often for long distances, in the belief that good technique can compensate for slowing down as he ages. He says he doesn’t know the word “can’t.” He has skied the Birkie with a fever of 103°. “The bug was burning out of my system,” he says about that race. “When I finished, my temperature was 96.” Improbably, he skied his 18th race with a dislocated shoulder.

Daily and in the big picture, St. Germaine’s decisions are guided by how they will influence his ski season. “I have a shoulder that needs work, and a knee, too,” he says. “When I have that work done, it will be one week after the Birkie so I’m ready for the following year.” He pays close attention to his resting and walking heart rates, and he records his pace when he skis. He does not eat white flour or added sugars. He’s always thinking about the race, especially now during the pandemic. “If I’m in a store, and people are there without masks, I think about my lungs,” he says.

Legacy in the Making

After his first Birkie, St. Germaine says he swore, “Never, ever, again!” But the next December, he says, “people were coming to Telemark Lodge to try this new way to ski, and they wanted lessons. The Nordic instructor needed help, and Tony Wise said to me, ‘You know how to ski. You’re a Birkebeiner. You will teach Nordic skiing.’”

St. Germaine didn’t have a chance to respond. “Tony walked away just expecting I’d never say no. And, of course, I never said no to Tony when he asked for anything.” That’s partly because Wise had honored Native Americans at the lodge, hosting ceremonies and providing jobs for tribal members. “I grew closer to my own identity because of how he made it possible for my mentors to demonstrate their pride in our cultural identity,” says St. Germaine. “Also, Tony’s pride in his own Norwegian identity and culture was an example for all of us.”

In college St. Germaine had played baseball, and he was a good hitter. He has a master’s degree in education and worked as a school administrator in curriculum development. He later attended the National Judicial College in Reno, Nevada, obtaining a degree in judicial law. While he was there, someone started offering courses in tribal law and spoke to him about Native philosophies. St. Germaine later went on to develop the curriculum for the college’s National Tribal Judicial Center. He has been a tribal judge, and he’s especially supportive of alternative sentencing. He believes in peacemaking as a response to any charge, in accord with a tribe’s traditions.

Details from most of his 47 Birkebeiners come easily and serve as an oral history of the race. A specific memory might be, “That was the first year we used klister, and it was warm and wet in the swamp. It was definitely not smooth and flat” or, “I saw the Quinn brothers ahead of me, skiing in perfect rhythm until they disappeared around a curve on the railroad grade.” And this gem: “The day before the 1976 race, it rained and then the temperature dropped. This was the first year we climbed up and over a downhill slope called Valhalla at Telemark Resort, before we descended on a run called Stormoen. Overnight, a groomer had broken up the frozen ponds that formed at the bottom of every hill, leaving clumps of ice. Stormoen was treacherous. I stood at the top of the run with Ingemar Sundberg, director of the ski school. I asked Ingemar, ‘What do we do?’ Ingemar said, ‘We tuck.’”

It’s no surprise to runner Billy Mills that St. Germaine is still skiing and mentoring young people on skis and parents, too. Mills won a gold medal in the 1964 Olympic Games, sprinting from behind in the 10,000-meter run. Mills is Oglala Lakota, from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, and he and St. Germaine have been friends since 1972. “I recognized something powerful in him when we first met,” says Mills. “I saw how he lived his life. Ernie had the wisdom of an elder even as a young man and used that to aspire to his own dreams. He speaks quietly and gently, and people listen. That is a sacred gift.”

Inspiring the Next Generation

Every winter, St. Germaine skis with his grandson Benjamin, who will soon be nine years old, in a program called Hayward Nordic Kids. He teaches a traditional parenting class called Family Circles on the Lac du Flambeau Reservation, for which he wrote the curriculum 30 years ago, and he’d like to see more Native parents involved with getting their children interested in skiing. “Just providing skis isn’t enough,” he says. “We have to bring families along with us. Kids need to have parents there with them, committed to their well-being.”

Benjamin loves to ski, and one can see in St. Germaine’s eyes that Benjamin is the light of his life—one that has eclipsed the Birkebeiner in importance.

In early August, St. Germaine emailed that he was embarrassed and ashamed that he’d ruptured his Achilles tendon. He’d first injured it while running back in the mid-1980s. After the 2021 Birkebeiner he strained it again, and he’d been struggling with it ever since. “I finally completely ruptured it but fortunately was able to have it surgically repaired within days,” he wrote. “My surgical nurse, just before I went under, said, ‘My parents ski the Birkie and are rooting for you.’”

By late August he was walking without crutches, wearing an orthopedic boot. A friend came by and St. Germaine waggled his leg in the air, showing off the boot and emanating optimism. “I’m lucky,” he said. “I have a long road to recovery ahead of me and, of course, I am motivated to return and ski the Birkebeiner but, more so, to ski alongside Benjamin again this season. He lifts this old heart up and helps it fly.”

This story first appeared in the Early Winter 2022 issue of Cross Country Skier (41.2).