The U.S.’s newest national monument is inextricably tied to ski history. When President Biden traveled to the central Colorado Rockies in October to announce the 53,804-acre Camp Hale–Continental Divide National Monument, he honored the troops of the U.S. Army’s legendary 10th Mountain Division.

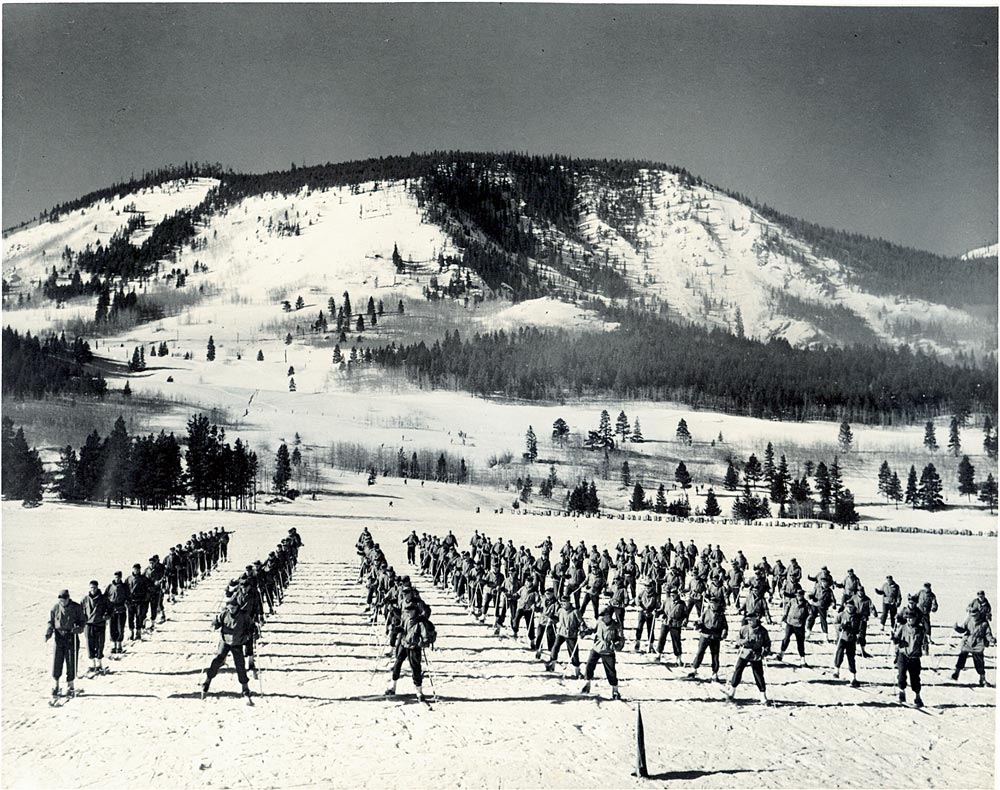

These skiing soldiers, who battled in Italy’s Appenine Alps near the end of World War II and broke through a significant German stronghold, trained at Camp Hale, which opened in November 1942, and in the nearby Tenmile Range. They learned how to cross country and downhill ski, rock climb and survive in harsh winter weather. Though many of the buildings were torn down in 1945, Camp Hale sporadically hosted other training, including for covert CIA missions, until it closed in 1965.

The same land is also cherished by the Ute Tribes, who were driven from their Colorado homelands in the early 1880s. Up until then, the Utes had come to this area annually to hunt and to gather medicinal plants, and it’s still a place where they honor ancestors.

The protected status is long overdue, believes John Morris, 92, who spent four years in the 1950s at Camp Hale as a civilian instructor for the army’s Mountain and Cold Weather Training Command. While there, he worked with soldiers from Colorado’s Fort Carson. The national monument designation will also provide more chances to communicate the area’s history as the only site ever developed by the army specifically for mountain and winter training.

“I don’t think the public was aware of the extent of what went on,” says Morris. “We sometimes went out for three or four days to bivouac. We were without tents most of the time, digging a snow cave and using fir boughs and trees. Eventually we got sleeping bags with down and air mattresses, and things got better.” Many of the troops had no previous mountain experience; some had never even seen snow before.

An effort to legislate special designation for Camp Hale, while continuing to permit recreational use, had been in the works since 2017. Some of Colorado’s congressional reps sought to make Camp Hale the country’s first national historic landscape as part of a broader public lands bill. As the bill stalled in the Senate, however, and the number of WWII vets dwindles, Biden used his authority under the Antiquities Act to protect the land via a different route.

The designation also recognizes the enormous influence 10th Mountain vets had on the then-fledgling ski industry. Post-war, they fanned out across the U.S. and established or managed more than 60 alpine resorts. Veterans also helped expand the outdoor recreation industry, among them, David Brower, the Sierra Club’s first executive director; Paul Petzoldt, National Outdoor Leadership School founder; and Fritz Benedict, creator of the 10th Mountain Division Hut System.

During World War II, Camp Hale housed 1,000 buildings on 1,500 acres in the Pando Valley and functioned as a small city. Today, with only a few crumbling foundations and some faded interpretive signs, there’s not much to see. But Nordic skiers know the area well. The trailhead for the Jackal and Fowler/Hilliard huts, both part of the 10th Mountain network, is here. The Tennessee Pass Nordic Center (outside the monument) lies just 6 miles southeast. And the valley floor provides miles of off-trail ski touring. Meanwhile, the Tenmile Range, a separate section of the monument that’s between Copper Mountain and Breckenridge ski resorts, has numerous ungroomed ski trails.

National monument status is no guarantee, as future presidents could roll it back (think Bears Ears and Grand Staircase–Escalante), but for now skiers can visit with a new appreciation for the history-makers who came before them.

This story first appeared in the Early Winter 2023 issue of Cross Country Skier (42.2)